by ILARIA SERRA

“Poor Christ,” Italian immigrant. The Italian saying refers to people who are unlucky and disgraced: Poor Christ… but in Italian American literature and art it has become a widespread metaphor, at least thanks to the foundational novel Christ in Concrete by Pietro di Donato, released in the United States in 1939 and translated as Cristo tra i muratori in 1957 (Mondadori). We will deal with this novel elsewhere. Here we focus on the paintings by Ralph Fasanella many of which use the image of the “poor Christ” by translating it into his own naïf or primitive iconography. Naïf does not mean trivial. In Fasanella’s case it refers to the strong immediacy of his style and to his being a self-taught artist. His paintings are open windows onto the Italian American life in the big city, New York, in the heart of the twentieth century, and are full of telling details for those who are able to read them.

Ralph (Raffaele) Fasanella was born in 1914 in the Bronx. His father Joseph was an iceman, a profession that disappeared with the arrival of modern refrigerators. His mother Ginevra Spagnoletti was a textile worker and political activist. Both parents were born in Andria, in Puglia. This social origin marks Ralph throughout his life and becomes the inspiration for his paintings. Aside from being an American baseball fan, he always felt like an immigrant and a worker. Ralph was a member of numerous leftist groups and workers’ unions. He took part in the Spanish civil war as a volunteer in the army against Franco in the 1930s. In the mid-forties he began to paint and draw, because he was trying to cure arthritis on his hands. The definition of artist is narrow and almost embarrassed him throughout his life. But he did spend all his life making art, painting strikes and demonstrations, daily commuters and factory workers, and crowded cities.

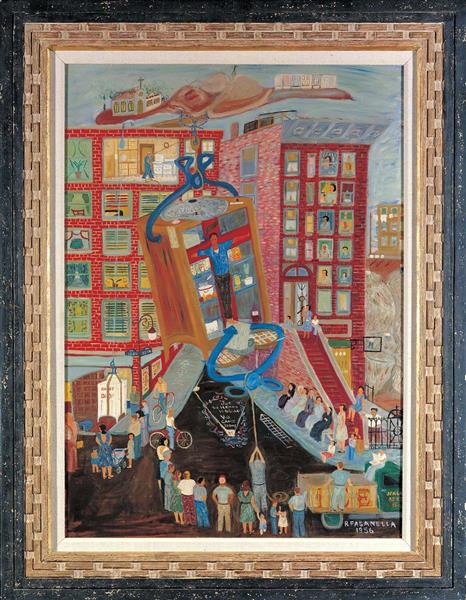

We focus here on some paintings that include a curious detail: his own lay Christ, who is a personal Christ (the portrait of his own father) and a universal figure (a worker like many others). In several paintings about life in the metropolis and its citizens, Fasanella inserts a crucifix where a worker hangs. In 1948 Iceman Crucified # 1, we are inside a skyscraper. A huge concierge room opens on the ground floor, breaking any law of perspective and proportion. On the side walls two rows of mailboxes, all rectangular, all anonymous, suggest the overcrowding of the building. The curtains of the upper floor windows are also anonymous, of different colors but all closed. The entrance space is occupied by a huge crucifix on which hangs a man wearing his work clothes, the iceman uniform: brown trousers, leather belt and blue shirt. Instead of a crown of thorns, his temples are clenched by the big iron tongs used to grab the ice, the tool of his work.

As an iceman, Ralph’s father would drive the cart down the streets of New York and bring ice into the homes. He would climb several flights of stairs with heavy blocks on his shoulders. He then arranged them in the iceboxes so that they would take up as little space as possible. This work translated into a pictorial style for his son: Ralph learned then, he said, to cram as many subjects as possible within the same canvas. On the iceman, however, hung a death sentence. With the arrival of modern refrigerators in the 1950s, this job became useless and disappeared. Such disappearance is documented in Iceman Crucified # 3. Here we are outside in the street. The traditional iceman’s cart appears in the lower right corner. The center of the picture is occupied by the symbolic death of a trade. The crucifix is inside an icebox that is lowered from above: it will be replaced by a brand new modern white refrigerator waiting on the left. This Christ rests on a block of ice and is pulled down by gigantic ice tongs. White chalk writes on the black asphalt: Joe the iceman is dead. No game today. The street numbers are no chances: 1887 is the birth year of Ralph’s father, and 1957 is the date of his return to Italy. It was the death date of his American dream. That year in fact, the father left his wife and children. America had chewed and spat him out. He returned to Italy as a destroyed man.

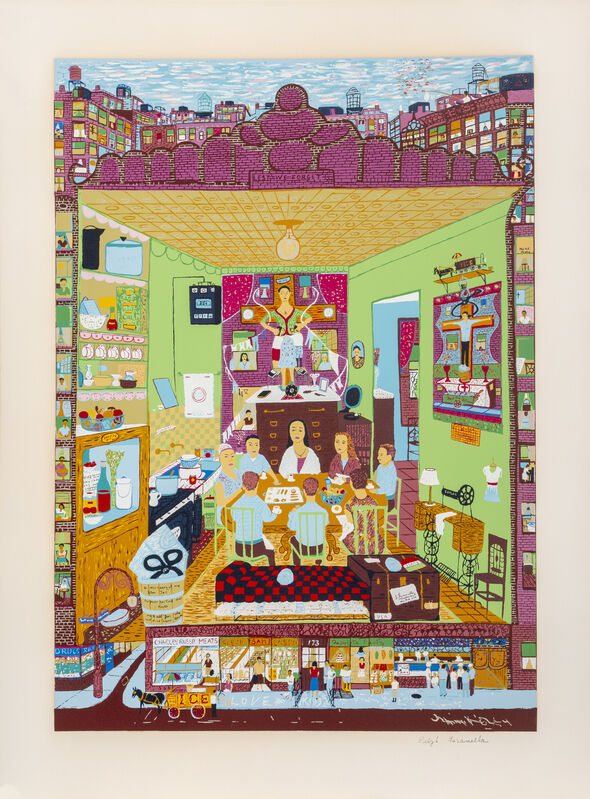

In 1972, Fasanella painted Family Supper in which the kitchen of his own apartment (on 143rd street) expands and occupies the entire space of the building. On the ground floor, there are the shop windows of a series of Italian American trades: Sam Sasso’s bottega, Charles Russo’s butcher shop, the greengrocer, the neighborhood bar. On the street, in the left corner, a horse-drawn ice cart. The streetlamp becomes part of the kitchen. On a bucket containing ice and tongs is written “In memory of my father Joe – poor bastard died broke – and to all Joes who died same – broke.” Note that being “broke” keeps the echo of being “shattered”: these poor Joes are broken by hard work and by American jobs. The kitchen is filled with objects and memories from Ralph’s daily life as an Italian American, including his mother’s sewing machine. In the center, the family huddles around the table, with the mother in middle. On a picture on the right appears the usual crucifix with the iceman wearing brown trousers and blue shirt, with his head gripped by the tongs and his feet resting on the ice block. Above him the iceman’s cart, below him the altar of the Eucharist.

Fasanella, who was baptized in the Church of Mount Carmel, and raised as a Catholic and a Communist among Jewish neighbors, returns to his ethnic religiosity, as an ineluctable Italian American cultural element. In his interview in the New York University digital library, Fasanella recalls his religious upbringing. He also remembers the pull towards the criminal world that dangerously appeared in the mind of every young Italian American in 1920’s New York. Some of Ralph’s friends in fact ended up on the electric chair.)

In his famous About Looking, art critic John Berger includes Fasanella as an example of an artistic reaction to the dehumanizing city. Berger notes that the city appears as a huge ship of immigrants in his overcrowded canvases: each apartment is a berth, each window is a porthole that isolates the individual. He also notes how Fasanella uses slits and windows as privileged impossible viewpoints to tell the stories behind such isolation. It is as if the painter forcibly opened the doors of History to allow the marginalized workers to enter. But above all, says Berger, Fasanella wants people to remember in a city that teaches to forget. New York demands that emigrants forget who they are, it exploits them and then sends them away to give space to the newcomers. In this dehumanizing city nothing remains. The job of the iceman melts like ice. “Lest we forget” is written on the ceiling of Family Supper.

Success smiled on Fasanella before his death in 1997, even if he who had painted pictures for public use started to see the slow disappearance of public meeting places such as workers’ clubs and trade unions. Political associations started to close, but his paintings – he demanded – were not to be locked up in a museum or in the living room of some rich man. In 2014, his works were brought together in a retrospective in the American Folk Art Museum, but Ralph’s art does not belong to a museum. It belongs to immigrants, the workers, the ordinary people, and the city spaces. Therefore, it is significant that his Family Supper is now hanging in one of the buildings in Ellis Island and that his Subway Riders is permanently embedded in the mezzanine of the subway station between Fifth and 53rd streets, in New York City.

On the cover: illustration by Massimo Carulli